After Addis Ababa, my next stop was Bahir Dar. It’s about an hour by flight from Addis Ababa—way easier than the 10- to 11-hour road journey, unless you’re in the mood for a very long African road trip.

Before I left Addis, I decided to walk around a bit in the morning. Let’s just say, solo walks aren’t always peaceful. I had a guy stalking me—he followed me wherever I went until another kind stranger stepped in. Classic travel moment: unsettling, but also heartening in the end.

On the flight, I met a talkative Ethiopian man named Hayleysus. Within 30 minutes, he told me I was lucky, and so was my (non-existent) husband. I smiled and received the compliment like a true diplomat.

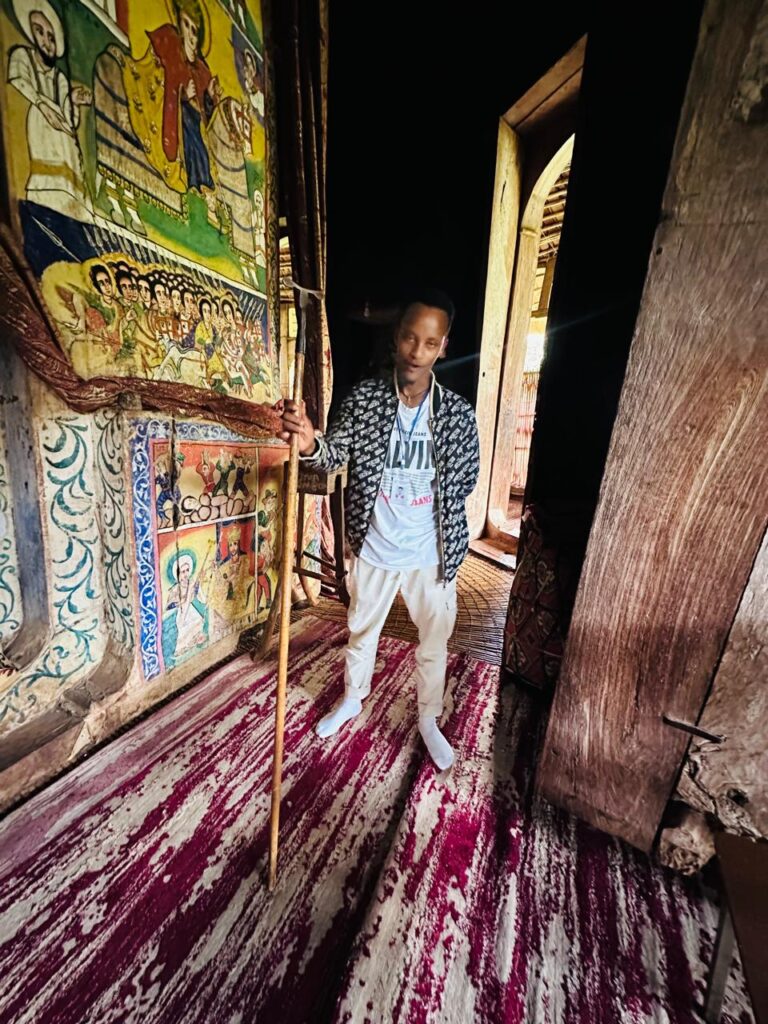

At Bahir Dar airport, I met my guide—Ababou. “Call me Aby,” he said, and I did. Aby turned out to be a walking-talking encyclopedia of Ethiopian history, culture, religion, and unexpected jokes.

He started right away, talking about Emperor Menelik II and the Italian invasion. Here’s the real story: In the late 1800s, Italy tried to colonize Ethiopia but was famously defeated at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, under the leadership of Emperor Menelik II and Empress Taytu. It’s one of the most important victories in African history and a source of national pride.

Then we got to Lake Tana, Ethiopia’s largest lake and the source of the Blue Nile. It’s 84 kilometers long and 66 kilometers wide, dotted with 37 islands, many of which host ancient monasteries. The lake is calm and mysterious—like it’s holding secrets beneath the surface.

Here’s something that fascinated me: The Nile River, the longest in the world, has two major tributaries—the White Nile, which starts in Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile, which originates here in Lake Tana. The two rivers meet at Khartoum, Sudan, and then flow northward to Egypt and finally into the Mediterranean Sea.

Why “Blue Nile”? The waters carry rich, dark volcanic soil during the rainy season, giving it a bluish tint—at least compared to the White Nile, which looks paler and carries less sediment.

As we boated through the lake, Aby pointed to a spot and said something I wasn’t expecting: “Jesus and Mary were here… they were in exile for 3 months and 18 days.” I raised an eyebrow. He explained it’s a widely shared oral tradition among some Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, though it’s not formally recorded in Biblical history. According to the local legend, during the reign of King Herod, they fled further than Egypt—reaching as far as Ethiopia. Is it myth or memory? I’ll leave that to the theologians. But it’s a beautiful thought.

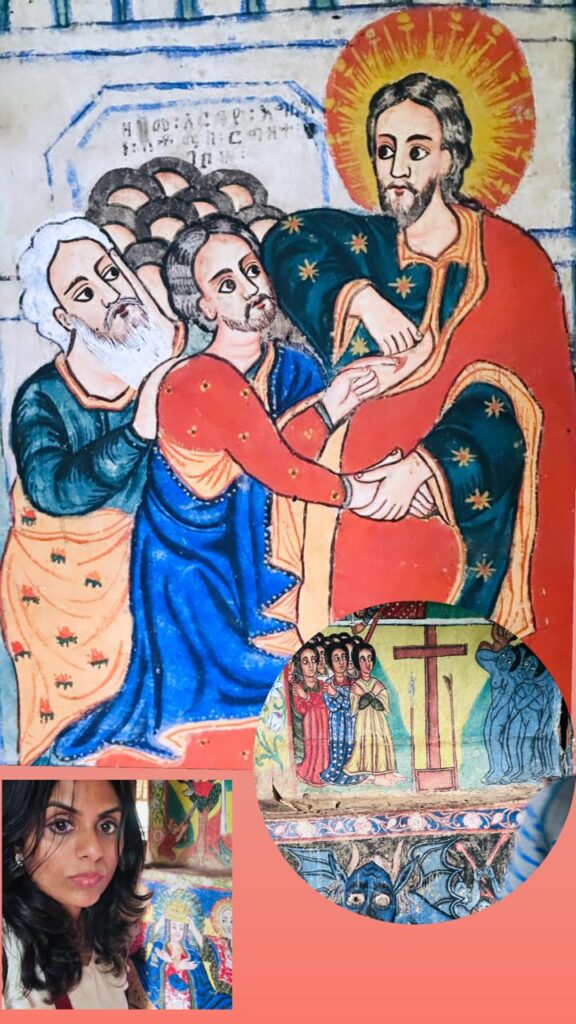

We visited Tana Qirqos Monastery, said to have housed the Ark of the Covenant at one point (yes, that Ark), and full of hand-painted murals and spiritual silence. These monasteries are serene, ancient, and deeply symbolic.

Did you know Ethiopia has two types of monasteries? United and societal. In United monasteries, it takes about three months to become a monk. They live in tight-knit, regulated communities. In societal ones, monks live more independently, and the vows are looser. Aby, being an Orthodox Christian himself, explained all this like he was taking me through his childhood memories.

He also told me something sweetly offensive. One of the monasteries—Kebran Gabriel, the closest to Bahir Dar—is not open to women. So, no entry for me. Monks believe that women bring distractions. (Don’t worry, I’ll distract them from outside.)

We explored the Zege Peninsula, home to several of these island churches. I remember visiting a church with round architecture, painted walls, and glass windows. Ethiopian churches usually follow four architectural styles: round, rectangular, cave-based, and rock-hewn—with the latter being iconic in Lalibela.

Inside one round church dedicated to Mary, I noticed three distinct areas: the chanting section (for hymns and prayers), the holy section (only accessible to priests), and the Holy of Holies, where only the head priest may enter. Aby explained that monks cannot marry, but priests can, as long as they marry before ordination. Once a priest is widowed, remarriage is not allowed.

Oh, and my boat driver’s name? Taju. Quiet man, good with currents.

Aby also talked about Timket, the Epiphany festival. It’s massive here. People reenact the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River. And there’s a curious tradition: during the celebration, men throw lemons at women they fancy. Aby said if I stayed, I’d be showered in lemons. I nearly replied, “I’d make lemonade,” but settled for a smile.

Toward the end of the ride, we reached the spot where Lake Tana meets the Blue Nile. I saw the first bridge built across the Nile in Ethiopia—an old stone structure standing proudly like a relic of ambition. Nearby, I spotted a young boy with cattle. I took photos of him. When he saw me, he blushed and smiled. That smile was worth more than any souvenir.

Lunch was lakeside—lovely food, many flies. But they placed a fan next to me, and somehow, that simple act felt luxurious.

I ended the day at the Haile Selassie palace viewpoint, watching the city of Bahir Dar glow under the golden sunset. Then it was back to the hotel.